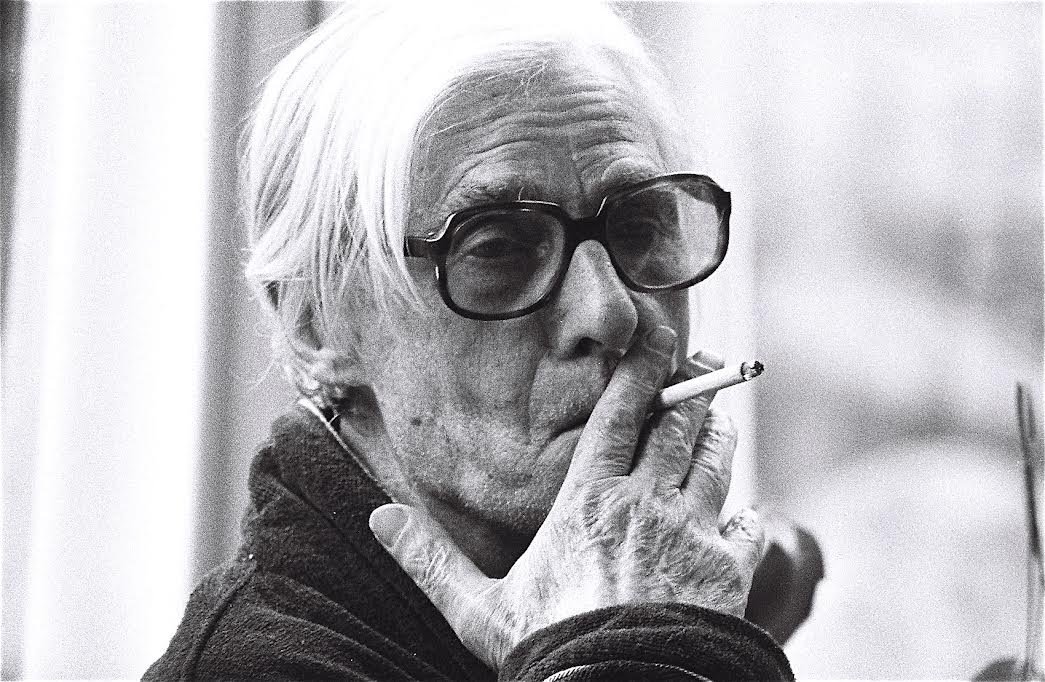

Robert Mangold #RobertMangold #artist

A Man in His Own Heaven

I was younger than young when I began entering the studios of artists. You should have seen me. I stood six-foot-three and as they say in the NBA, “ready to go to the hoop”.

My time on the streets of New York was focused on carving out a career as a photographer. My playgrounds in NYC were never traditional. They were habitats of others.

I felt as if I had on elevated “toe shoes” when I entered Willem de Kooning’s studio. My gawky gait wouldn’t suggest to anyone that I could dance in the ballet. Nor did I ever own a pair of toe shoes. Psychologically I tried to imagine a more suave presence. It didn’t work. The church of my new life was suddenly overwhelming. My shoes were whispering for me to relax. Not only was de Kooning among the most famous living artists, but he was my first recognized portrait.

#willemdeKooning #artist #abstractexpressionsism

I cannot overstate the feeling. I felt as if I was in an unparalleled universe ala Marc Chagall’s floating dream. Profoundly religious air made me timid and alive. I was handling paintings and sculpture by the most famous artists. That day I caressed de Koonings’. The gods of modern art were waiting for me to make my camera go “snippety snap snap snap”. I was entering a description of my descriptive memory.

My memory of photographing artists is like a Queen bee or a Beyoncé BeyHive; remembering the names of the 80,000 or 80 million worker bees is impossible. Yet the stories never cease to enliven my day. If I were to die after my last artist portrait, I would say that I died “a man in my own heaven”.

I lived in the church of art for ten years.

I found something as a photographer. I realized at twenty-five that if I could hear the music, I would find the picture. I started not only to see, but listen. Listen to what the artists’ shared but also listen for the music. The words, the music, the space and film became my own Rubik’s Cube.

I have continued to spin for forty years. I am not Yo-Yo Ma.

One evening I was making snaps of Yo-Yo Ma. I asked him when does he practice. He said that he performs Three-Hundred and Sixty-Four days a year; That’s his practice routine. Now of course I am no Yo-Yo Ma but I have never missed a day even taking a snap.

Photographing artists’ lives has been a symphony of amalgamated sounds. The studios neither resembled a Sunday Gospel nor any diagram of lines and spaces on a musical stave. Music became my preeminent way of movement towards my subject. Music became my preeminent way of comprehending where I was. Music became my “ Star Trek”: “Where no man has gone before”. Music traveled through my eyes and into the moment. If you have known hallucinogens in any context, then you know.

Sandro Chia (who I have photographed three times) always had something echoing through his vast studios in New York and Italy. David Salle who posed twice was master of the classical seduction.

Jeffrey Koons and Robert Longo tunes had bombastic bass drums influencing something.

Hockney was losing his hearing, but his Mendelsohn rested my soul. The temples of Reuben Nakian, Larry Rivers, Henry Moore, Claes Oldenburg, Rauschenberg and hundreds more echoed sounds of change. This very young naivet was along for the ride.

#JonathanBorofsky #artist

#Robert Therrian #Roberttherrian and #Juliabrownturrell

One day, I photographed Jonathan Borofsky, Robert Mangold and Robert Therrian. I realized there was a certain photographic motif reigning in my world. It was time to step aside and move on. I was done.

I left their studios with a little “Cheshire” from ear to ear. Ten years of photographing artists was an incredible introduction into the church of art, and the music that developed my photographer’s sway.

#peterBlume #artist #american #surrealist