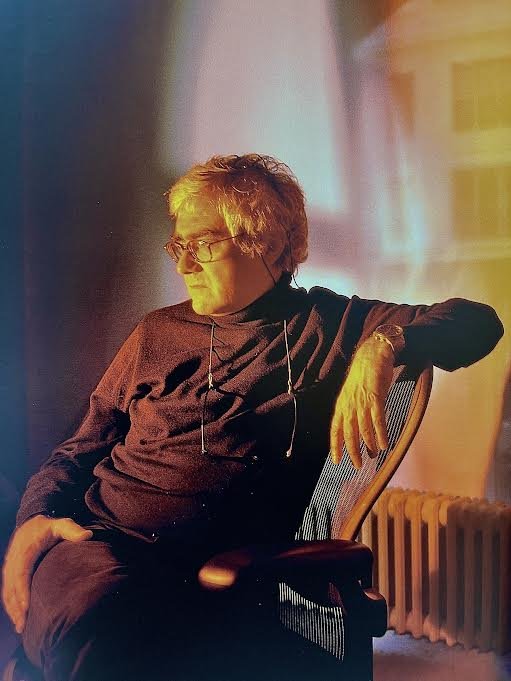

Rafael Vinoly 2004

Rafael Vinoly

I have used film for my photographs for five decades. Film always reminds me of books I have read.

The memory of a book on bookshelf is a connection to things I have learned the things I have seen, things I have felt. One book cover allows me to recall a hundred parcels of passages that were meant for just my eyes, just my heart.

I can look at my acid-free photography archival notebooks and speak about each frame hidden among them as if the photo was made today or fifty years ago. Each transparency has a ten thousand word essay attached. My memories go places that are clearly present. The memories take me places so riveting that I can feel a hand I touched or see the color of a sky that I have not seen in decades.

When people die who have lived in my archives for a day or a decade, a part of me vanishes into a Bardo or a free ride along the River Styx. Funny, never above the clouds.

The lives of others live in some form of chrome: Kodachrome or something grander or even smaller. The life of others Iive with me every waking moment.

When the great Fred Astaire died my mind hovered somewhere, recalling the lunch by his pool. When the great Gene Kelly died, I just kept thinking about the hot dog barbecue I did not attend.

The events seemed insignificant at the time; But time changes the way we see our past, present and future in mysterious ways. Sometimes the emulsion shifts on those chromes, the memories remain,

They are life builders: Some of the most significant days of my life.

When death stands before me, I feel something broken in me. I want to recast the past, and make the past the present. Oh well, I am not Galileo or Einstein imagining the way we should observe the physics of the universe. I am just a guy who can remember every gesture, every space and every shard of light that lives on my film in my life. I just have a hard time letting go of my past. Even if I were to destroy the tens of thousands of images there is not a frame I would forget.

Vinoly’s Walkie Talkie:The Fenchurch Building

I was not close to the architect Rafael Vinoly. We met through the New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp. I met him again when he reigned with Frederic Schwartz over the “Think”

Group for the rebuilding of the World Trade Center.

Vinoly’s Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts

I met a hundred architects in those times. There was something about Rafael. I went to his office to shoot his portrait for my book “Portraits of the New Architecture”. He understood the process. My process. I was documenting the world of architecture and the people who designed it.

While shooting, I realized I could have stood Vinoly on two naked donkeys braying David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” and Rafael would have still gone along with my session. It was the same for Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly: they wanted to participate in my world.

When I read the Rafael Vinoly New York Times obituary, I was shaken, not because of a friend lost, I did like him as a person and an architect) but a unique and possibly a crucial piece of my world vanished.

The event reminded me of the Chinese game “Go”. “Go” is a strategic game. “Go” is a game where momentum is realized and rewarded. My life’s creation of thousands of playing parts (transparencies and negatives) has been about wild strategies and pivotal momentum. Possibly thousands of moves live within the game “Go”. Think about what the loss of a single piece, a single player in the game means.

Vinoly’s 277 Fifth Avenue dancing with the Empire State Building